Learning eBPF - Chapter 1: Why the Linux Kernel Needed eBPF?

TL;DR

This blog is based on the book Learning eBPF by Liz Rice.

The book gives a clear understanding of what eBPF is, why it was created, and how it works inside the Linux kernel.

If we really want to understand what is happening inside a Linux system, we need to look inside the Linux kernel.

But touching the kernel has always been dangerous. Even a small bug in kernel code can crash the entire system and make it inaccessible. On top of that, kernel changes take years to reach production systems, and in cloud environments we often don’t even know which server our code is running on.

For a long time, this forced an uncomfortable tradeoff: stay safe and blind, or be powerful and risky.

eBPF exists because this tradeoff was no longer acceptable.

A Short History of BPF and the Evolution of eBPF

eBPF stands for extended Berkely Packet Filter.

Originally, BPF was introduced as a simple and efficient way to filter network packets. Programs were written using a small instruction set that closely resembled assembly language, and they could decide whether a packet should be accepted or rejected.

This early version is often called classic BPF (cBPF). While useful, it was limited in scope and mainly focused on networking.

Over time, Linux systems evolved, and the need for better observability, security, and performance became more important. This led to the evolution of cBPF into eBPF.

eBPF brought major improvements:

- • Better support for 64-bit systems

- • A rewritten and more efficient execution model

- • The introduction of eBPF maps, which allow data to be shared safely between kernel space and user space

- • A growing set of helper functions that let eBPF programs interact with kernel features

One of the most important additions was the eBPF verifier. Before an eBPF program is allowed to run, the verifier checks that it is safe. This ensures the program cannot crash the kernel, run forever, or access memory in unsafe ways.

Another key milestone was the ability to attach eBPF programs to kprobes. Kprobes allow instrumentation of almost any instruction in the kernel. Support for attaching eBPF programs to kprobes was added around 2015, which greatly expanded what eBPF could observe.

By 2016, eBPF was already being used in production systems. Brendan Gregg’s(btw check his work it's too good) work on performance tracing at Netflix helped make eBPF widely known, often describing it as giving “superpowers” to Linux.

Soon after, major projects began adopting eBPF:

- • Cilium used eBPF to build high-performance container networking

- • Katran , an open-source project from Facebook, used eBPF for scalable Layer 4 load balancing

As adoption grew, eBPF became a separate Linux subsystem, with contributions from hundreds of kernel developers. Over the years, limits such as maximum instruction count were increased significantly, allowing much more complex and powerful eBPF programs.

Today, eBPF is no longer just about packet filtering it is a general-purpose, safe, and high-performance way to extend the Linux kernel.

Kernel vs User Space

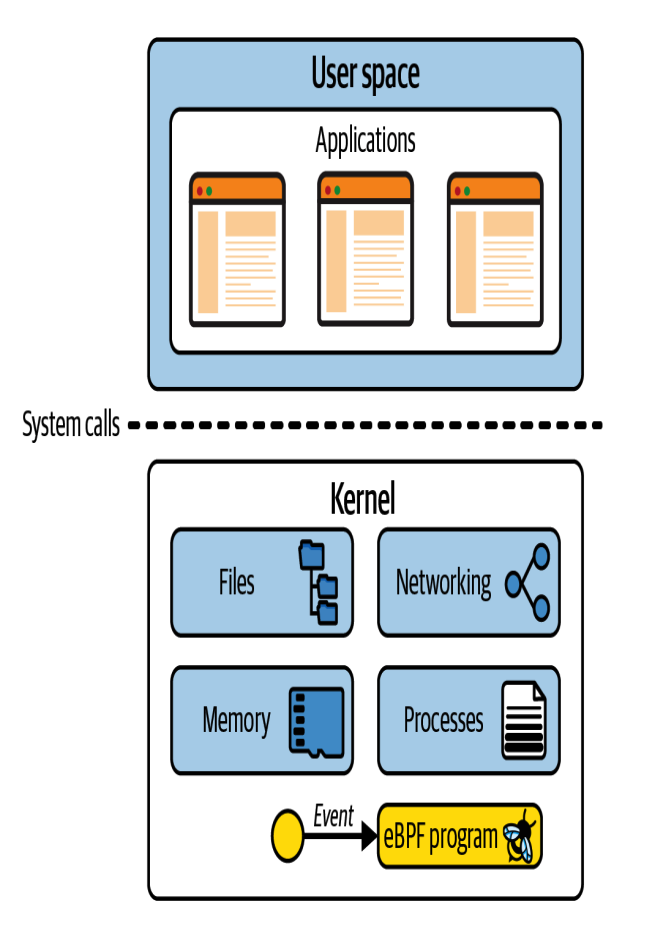

To understand eBPF, we first need a clear understanding of the difference between the Linux kernel space and user space.

The Linux kernel space is the software layer between applications and the hardware they run on. Applications run in an unprivileged layer called user space, which cannot access hardware directly. Instead, applications make requests to the kernel using system calls (syscalls). These syscalls act as an interface for the kernel to perform actions on behalf of applications.

Hardware access involves many operations such as reading and writing files, sending or receiving network traffic, and accessing memory.

This is how the coordination between user space and kernel space looks:

As application developers, we usually don’t use system calls directly. Programming languages provide high-level abstractions and standard libraries that hide these details.

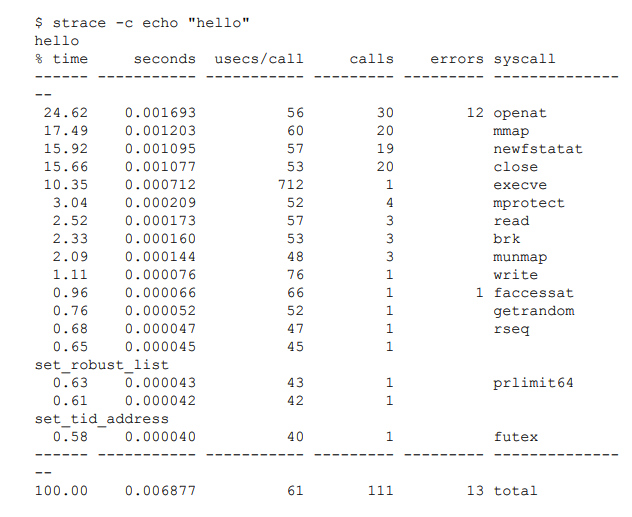

Because of this abstraction, we are often unaware of how much work the kernel is doing while our programs run. To understand this better, we can use tools like strace, which shows all the system calls made by an application.

For example, even a simple command like using cat to print the word hello involves more than 100 system calls:

Since applications heavily rely on the kernel, observing their interactions with the kernel can teach us a lot about application behavior.

Why Kernel Changes and Modules Are Risky?

The Linux kernel is extremely complex, with more than 30 million lines of code. Making changes to such a large codebase requires deep familiarity with existing code, which makes kernel development challenging for most developers.

Contributing to the Linux kernel is not just a technical challenge, but also a social one. Since Linux is a general-purpose operating system used everywhere, changes must be accepted by the community especially Linus Torvalds as beneficial for the ecosystem as a whole.

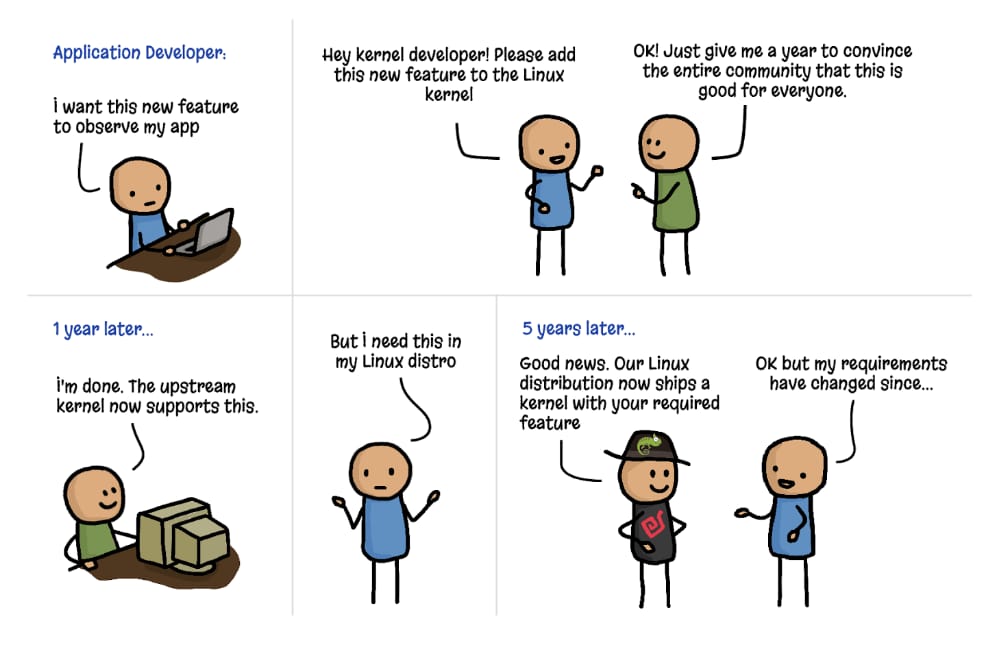

This is not easy. Only about one-third of submitted kernel patches are accepted.

Even after a technically sound change is discussed, developed, and merged, it does not reach users immediately. Although Linux releases a new kernel every two to three months, most users rely on distributions like Debian, Red Hat, Alpine, or Ubuntu, which ship older and more stable kernel versions. As a result, an accepted kernel change can take years to appear in real production environments.

As shown in the illustration below, it can literally take years for new functionality to go from idea to production:

Kernel Modules

Since adding features directly to the kernel takes so much time and effort, kernel modules offer an alternative. Kernel modules can be loaded and unloaded on demand and allow developers to extend or modify kernel behavior without changing the core kernel. They are independent of the official Linux kernel and do not need to be accepted into the upstream codebase.

However, this introduces a major concern: are kernel modules safe to run?

How can we be sure that a kernel module does not contain vulnerabilities that attackers could exploit? How can users trust that a module does not include malicious code?

Because kernel code runs with full system privileges, any vulnerability or malicious behavior can have serious consequences. This is one of the main reasons Linux distributions take a long time to adopt new kernel releases.

eBPF offers a very different approach to safety. The eBPF verifier ensures that an eBPF program is only loaded if it is safe to run. It guarantees that the program cannot crash the system, enter infinite loops, or compromise system data.

Dynamic Loading of eBPF Programs

eBPF programs can be loaded into and removed from the kernel dynamically. Once attached to an event, they are triggered whenever that event occurs.

For example, if an eBPF program is attached to the file open syscall, it will run whenever any process opens a file. It does not matter whether the process was already running when the program was loaded.

This is a major advantage compared to upgrading the kernel, which usually requires a system reboot.

Because of this, eBPF-based observability and security tools can instantly gain visibility into everything happening on the system.

Developers can create new kernel-level functionality quickly using eBPF, without forcing all Linux users to accept the same kernel changes.

High Performance of eBPF Programs

eBPF programs are a very efficient way to add instrumentation. Once loaded, eBPF programs are compiled using a JIT compiler and run as native machine instructions on the CPU.

Additionally, eBPF programs avoid frequent transitions between user space and kernel space, which are expensive operations. This makes eBPF suitable for high-performance observability and security use cases.

Why Cloud-Native Makes This Worse?

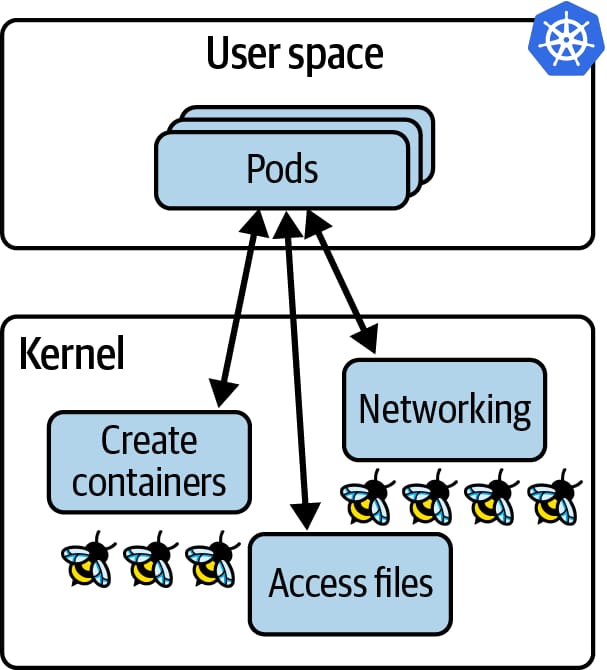

Earlier, I assumed organizations ran applications directly on their own servers. In reality, most modern systems run on cloud orchestration platforms like Kubernetes, ECS, or serverless platforms such as Lambda, Cloud Functions, or Fargate.

In these environments, workloads are scheduled automatically, and in serverless setups we often don’t even know which physical server is running our code.

Because of this abstraction, traditional host-based or application-level instrumentation becomes difficult. We often do not control the servers, cannot predict where workloads will run, and cannot easily modify application code or deployment configuration.

This is where eBPF becomes powerful.

Since eBPF programs run inside the kernel, they automatically have visibility into all processes running on a node whether they belong to containers, pods, or serverless workloads.

Combined with dynamic loading, eBPF-based tooling provides major advantages:

- • Applications do not need to be modified

- • Kubernetes YAML and configuration do not need to be changed

- • Already running workloads can be observed immediately

This gives eBPF-based observability and security tools a unique superpower in cloud-native environments: deep system-wide visibility without touching application code, pod lifecycles, or orchestration logic something sidecar-based approaches cannot fully achieve.

Summary

This chapter explains why interacting with the Linux kernel has always been difficult and risky, and how eBPF changes this by providing a safe, flexible, and high-performance way to extend kernel behavior. It sets the foundation for understanding how eBPF works and why it has become so important in modern systems.

And there is lot more to learn and understand about the eBPF and kernel in the upcoming chapters. So I try to keep them simple and easy to understand without disrupting the actual context from the book